Vehicle Actuation Control for Autonomous Driving

This page is a technical note about how to control a ground vehicle for autonomous driving.

Warning: This page is under a heavy construction!!! Come back later or use any parts of this page at your own risk.

Regulating Vehicle Actuation Commands for Autonomous Driving

1. Introduction

Before delving into learning about the topic of vehicle control, the very first question we should ask ourselves is what it is to control a vehicle? or what does that mean by regulating actuation commands of a vehicle and even for autonomous driving? Before throwing an answer to this, let's think about, for a moment, how we, as human, does driving a car, particularly parts related to manipulating actuations like steering wheel, acceleration, and braking. Why? Because we want to invent something to replicate what human is doing. When we begin to drive, for most of the cases, we gently

- press accelerator to make car begin to drive,

- press accelerator and brake in turn while cruising through traffics until reaching a destination,

- press brake to make car a full stop at the destination.

What I just described is an aspect of our daily, manual driving that we control/regulate the actuation of our cars as we follow a virtual path to the destination. You can think of the virtual path as a result of route planning we do before driving the car and can also be an imaginary line we drive our car to follow while driving on roads. Let's call, for now, this virtual path as a reference trajectory. We drive our cars to overlap our actual trajectory close to the reference trajectory as possible as we could. In other words, we control the actuators (i.e., steering wheel, accelerator, and brake) of our vehicle to follow the reference trajectory. A trajectory is the path that an object in motion follows through space as a function of time. See the trajectory to learn more about it.

Given this, we now have something to answer the question we asked to ourselves earlier.

What is it to regulate the actuation commands of a vehicle for autonomous driving?

In laymen's terms, it is to control/regulate the values of the vehicle actuation commands to minimize the difference between the reference trajectory and the actual trajectory. At this point, you might want to ask where does this reference trajectory come from and what does this have to anything with autonomous driving? In a typical architecture or the architecture that I have in mind for a self-driving car, the reference trajectory is typically provided by a vehicle behavior planner or a motion planner. For example, given traffic conditions reported and the current position by a perception stack and the map of area, a behavior planner might switch back and forth different driving modes (e.g., ``driving down road," ``handling intersection," etc.) and based on a driving mode, ``driving down road," for example, a motion planner generates an optimal trajectory for the vehicle to drive to a stopline of the next intersection. Given this trajectory or the reference trajectory, the goal of a controller is to generate a series of the actuation commands that minimize the difference between the reference trajectory and the actual trajectory.

2. Vehicle Actuation Control for Autonomous Driving

2.1 Vehicle Models

Developing a good controller is to start from modeling vehicle's dynamics and constraints. Having a good model of vehicle enables us to analyze and tune the controller more efficiently. The vehicle model what we're referring to is a mathematical model that describes how the vehicle moves. To describe how a vehicle moves, we can first talk about the kinematic model. The kinematic model is a simplification of vehicle dynamics that typically ignores many important physic elements like gravity, mass, tire forces, etc., but it's relatively simple and performs well in practice. Whereas a dynamic model captures a vehicle's motion in the real-world that incorporates tire foreces, longitudinal and lateral forces, inertia, grativity, air resistance, drag, mass, the geometry of the vehicle, chassis suspension, etc. Note that more realistic models are more complex and more challenging, but not necessarily guarantee a better performance. Thus, in practice, there is always a trade-off to make, depending on the application.

2.2 Representation of Vehicle Models

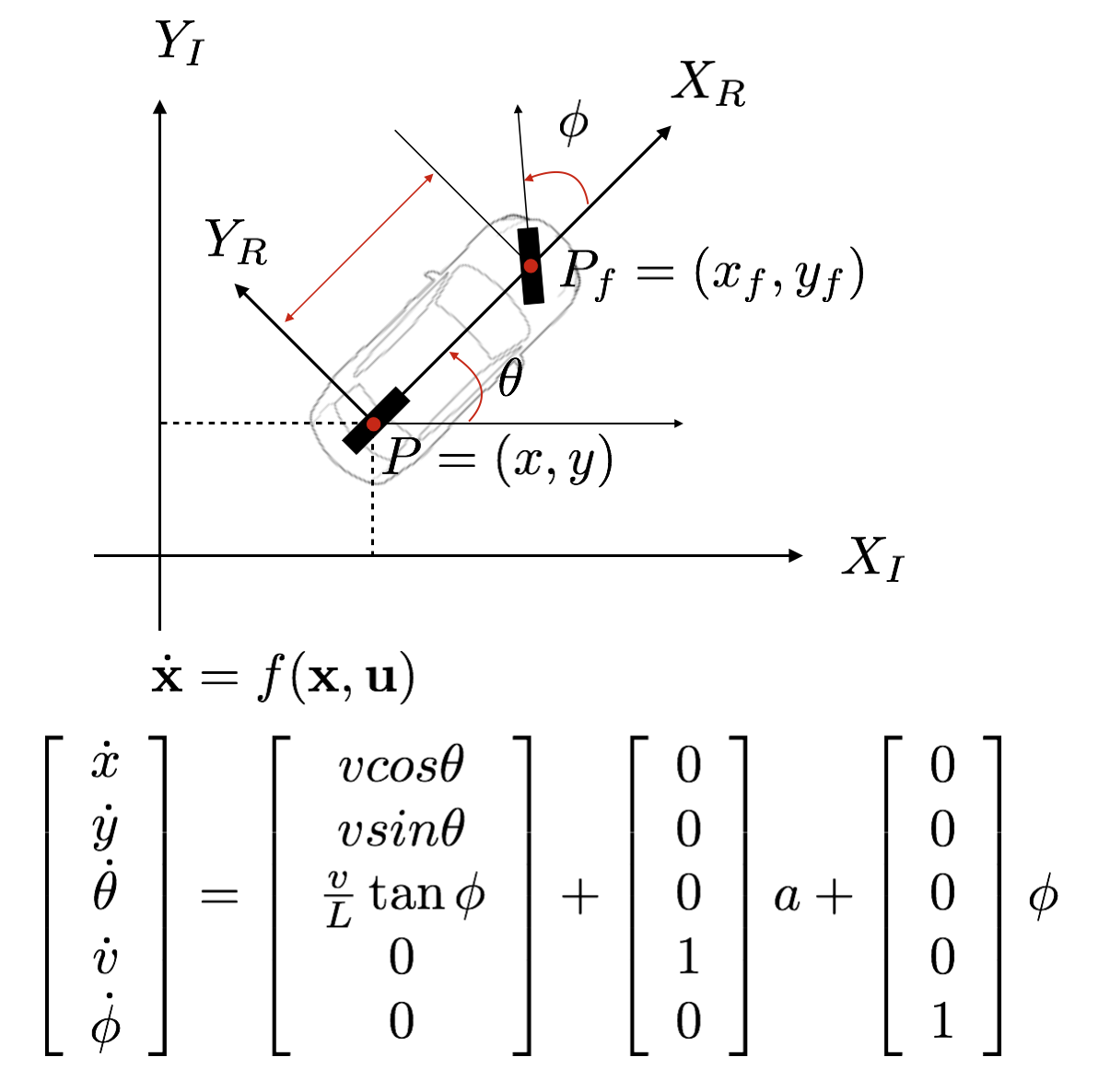

The state of a vehicle typically represents its position x and y, orientation theta, velocity v. The following figure illustrates a kinematic model (aka bicycle model) and its differential equation. The differential equation tells us how the state is changed over time.

where u is a control input for an actuation command that consists of a for acceleration both positive and negative and phi for steering angle. A ground vehicle typically has three actuators: steering wheel, throttle and break pedals. For the simplicity, one variable is used to represent two of those actuators, throttle and break pedals, together and change the values of throttle and break pedals together as in + for throttle and - for break pedals.

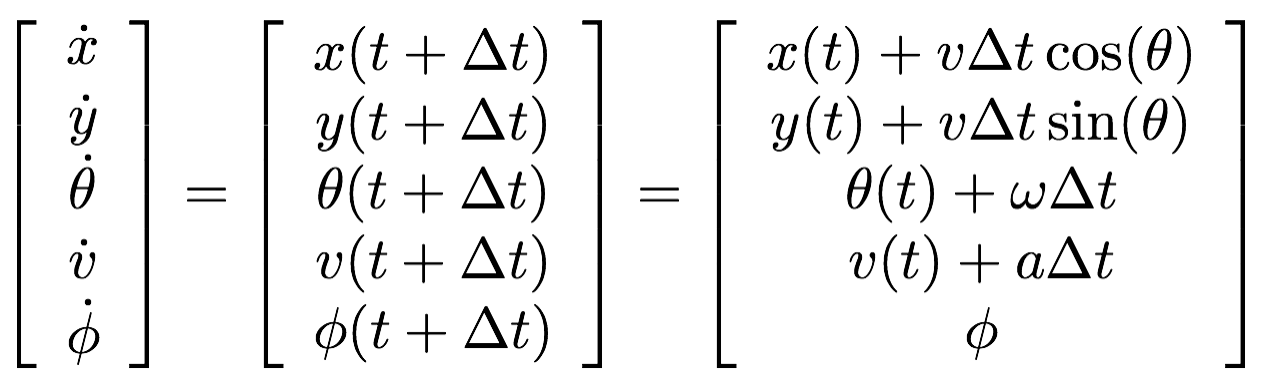

For an actual implementation, we need to represent such a differential equation in a continuous time into a discrete one.

where omega is the heading rate of change or angular rate and defined as v/L tan(phi(t)) and v is updated by v = v + a*dt.

2.3 Controllers as Error Minimizing Algorithms

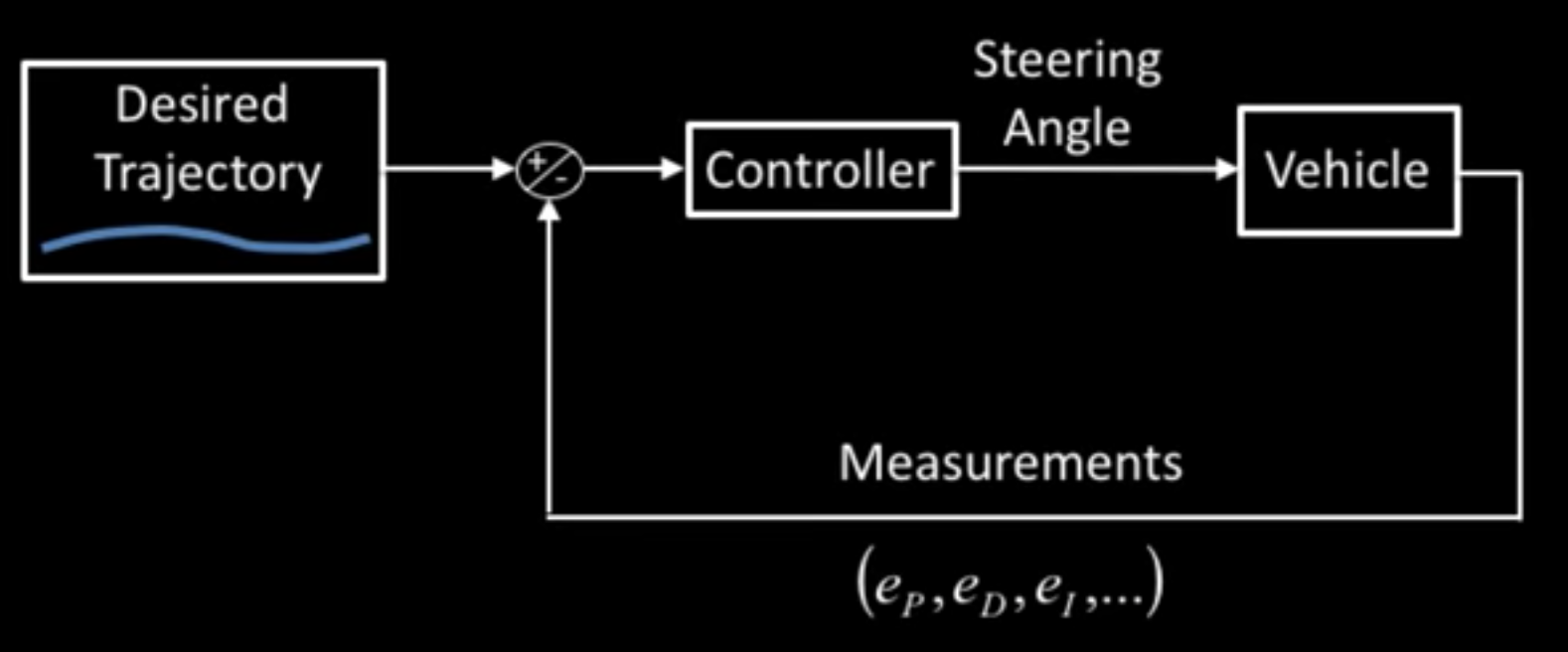

In a typical architecture of self-driving car, a behavior planner sets the goal of a vehicle (e.g., drive through a lane and stop at the stop line of an intersection). Given a motion goal, map, vehicle location, information about other neighboring objects, a motion planner generates a collision-free, trajectory that is optimal to the vehicle's dynamics. Given this reference trajectory, a controller regulates the outputs of actuators to follow the trajectory.

How does a controller actually do this -- regulating the outputs of the actuators to follow the reference trajectory? It does that by minimizing the area between the reference trajectory and the vehicle's actual driving path. Specifically, one can minimize this error by predicting the vehicle's path and then adjusting the control inputs to minimize the difference between the prediction and the reference trajectory. This is where one can use a kinematic model to predict the vehicle's future state. Once you've predicted the error you can actuate with the vehicle to minimize the error over time.

Thus the goal of developing a vehicle controller is to develop a controller that minimizes the distance between the predicted position of a vehicle and the corresponding position at the reference trajectory. This error between a predicted location and the corresponding location at the reference trajectory is called the cross track error (CTE). We also want to minimize the difference between the predicted heading/yaw and the actual one at the reference trajectory. We call this the heading/yaw error. Note that the speed is not something we want to minimize. If we do, we would end up minimizing the speed below zero and driving in reverse, possibly.

2.4 Errors to Minimize

Let's look at how the errors are changed over time by deriving our kinematic model around these errors as our new state vector, [x,y,ψ,v,cte,eψ]. Let’s assume the vehicle is traveling down a straight road and the longitudinal direction is the same as the x-axis -- the body frame of which the z axis is up.

For this example, the CTE is the error or difference between the center of the road and the vehicle's position. The CTE of the successor state after time t is the state at t+1 that is defined as: cte_{t+1} = cte_{t} + vt∗sin(eψ_{t})∗dt, where cte_{t} can be expressed as the difference between the line and the current vehicle position y. Assuming the reference line is a 1st order polynomial f, f(x_{t}) is our reference line and our CTE at the current state is defined as: cte_{t}=y_{t}−f(x_{t}).

If we substitute cte_{t} in the original equation with the above definition, cte_{t+1} = y_{t} − f(x_{t})+(v_{t}∗sin(eψ_{t})∗dt). This helps us to brake the cte_{t+1} into two parts:

- y_{t} − f(x_{t}) being current cross track error.

- v_{t}∗sin(eψ_{t})∗dt being the change in error caused by the vehicle's movement.

Now let’s take a look at the orientation error: eψ_{t+1}=eψ_{t}+(vt/Lf)∗δt∗dt. The update rule is essentially the same as ψ. eψ_{t} is the desired orientation subtracted from the current orientation eψ_{t}=ψ_{t}−ψ_{des_{t}}. We already know ψ_{t}, because it’s part of our state, but we don’t yet know ψ_{des_{t}} (desired psi) - all we have so far is a polynomial to follow. ψ_{des_{t}} can be calculated as the tangential angle of the polynomial f evaluated at x_{t}, arctan(f'(x_t)). f′ is the derivative of the polynomial. eψ_{t+1}= ψ_{t} − ψ_{dest}+(vt/Lf∗δt∗dt). Similarly to the cross track error the orientation error, eψ_{t+1} can be broken down in to two parts:

- ψ_{t} − ψ_{des_{t}} being current orientation error.

- vt/Lf∗δt∗dt being the change in error caused by the vehicle's movement.

3. Proportional, Integral, Derivative (PID) Control

We just reviewed what control of vehicle actuations is roughly about. Now let's take a look at one of the well-known control algorithms: PID (Proportional, Integral, Derivative) control. For the vehicle actuation control, what it is meant by developing a PID controller is to tune three gains so that the output of a PID controller minizes the error like CTE or heading.

The PID controller is a type of the closed-loop, feedback controller. Specifically, given a setpoint/reference value, a controller produces its output as a weighted sum of the P,I,D gains and corresponding error terms, and compares the measured, output value to the reference value, in order to produce its outputs close to the reference value. The goal of the controller is to eliminate the error or difference between its output and the reference value. Thus, a design of a PID controller typically involves in

- Defining each of three error terms and

- Finding the optimal values for the P,I,D gains that influences the controller's outputs.

double kp = 0.1;

double ki = 0.0001;

double kd = 1.0;

void PID::UpdateError(double cte) {

// integrate the error

sum_cte += cte;

// proportional term

p_error_ = - kp * cte;

// integral term

i_error_ = - ki * sum_cte;

// derivative term

d_error_ = - kd * (cte - prev_cte);

prev_cte = cte;

}

double PID::GetPIDOutput() {

return (p_error_ + i_error_ + d_error_);

}

where kp, ki, kd are the P,I,and D gains, the UpdateError() function defines how three errors, "proportional", "integral", and "derivative" are used in a discrete way, and the "GetPIDOutput()" generates a weighted sum of three error terms, which, for example, can be the control's output for the steering wheel value. For this example, more specifically, given the previouse cte, the function, ``UpdateError()'' computes the errors for each of three gains and ``TotalError()'' returns a new PID output minimizing the difference to the reference value.

Now let's take a look at each of the gain terms of a PID controller in details.

3.1 Proportional Term

The proportional term is a multiplicative scale factor to the error (e.g., CTE) where is the difference between the reference value and the control output. The controller's output, e.g., steering angle, is generated by output = Kp x e_{P} where "Kp" is the proportional gain (or scaling factor) that can be positive and negative and "e_{P}" is the cross track error (at the current car location).

The role the proportional term plays is to adjust the control output in proportion to the cross track error -- the bigger (or smaller) the error the larger (or smaller) the control output is. Because of this multiplicative nature, the smaller the proportional gain, the smaller the steady state error. And the larger the proportional gain, the more likely the loop is to become unstable. Thus, the proportional term, if it is used alone, would eventually make the controller overshoot, leading to oscillation.

3.2 Derivative Term

To correct such a potential overshooting by a P-controller while ensuring the controller to minimize the error, one could introduce two more error terms: the derivative, "D" and/or the integral term, "I." The derivative term models the error rate. It is more like an estimate of the upcoming error based on its current rate of the error change. For the case where one want to control the car to drive on the centerline of the road, assuming the reference trajectory is set along the centerline of the road, the cross track error rate captures how fast the car is driving in the perpendicular/lateral direction. If the car perfectly follows the reference trajectory, this rate would be zero. By adding this derivative term, the controller's output becomes, steering angle = Kp x e_{P} + Kd x e_{D}, where "e_{D}" is the derivative error and "Kd" is the derivative gain. In a discretization form, the cross track error rate can be approximated by "e_{D}(t) = (cte(t) - cte(t-1)) / dt" where "t" is the current discretization time, "t-1" is the previous time, and "dt" is how much time elapses between two consecutive measurements.

Now we have two gain factors to find their optimal values, in order to eliminate the difference between the reference value and the control's output. If we increase "P" to make the car close to the reference trajectory, the controller will eventually overshoot. To prevent this from happening, we could increase the derivative gain to increase the resistance of speeding to close to the reference trajectory. Note that in general the low "D" gain makes the controller "underdamped" to make a car be oscillated whereas the high "D" gain makes the controller "overdamped" resulting in a slow convergence. A good "D" gain will make the controller "critically damped."

3.3 Integral Term

Often, these two error terms are not good enough to generate a desirable control output because there are other sources of errors: environmental factors, mechanical defects, etc. These factors will change the nominal behavior of a vehicle, thus the performance of the controller. Suppose that the a PD controller manages the cross track error close to zero. While driving on the reference trajectory, the car drives over the piles of rocks. This event would make the car off from driving on the reference trajectory. The zero steering angle commands would be no longer keep the car on the reference trajectory.

So the "integral" term, I, is introduced to accumulate the

cross track error over time in order to check how much time

the car spends which side of the track. Like other gains, the

gain of the integral term has a side effect: with a low I gain

it will take a long time for the controller to generate a

desirable value. Whereas a high I gain will make the

controller fluctuate. steering angle = Kp x e_{P} + Kd x e_{D}

+ Ki x e_{I}.

Source

Source

In summary, the proportional term corrects instances of error, the integral term corrects the accumulation of error, and the derivative term corrects the error based on the change error rate.

4. Model Predictive Control (MPC)

5. Summary

Reference

Some of the good papers to read are- [Kong et al., 2015] J. Kong, M. Pfeiffer, G. Schildbach and F. Borrelli, Kinematic and dynamic vehicle models for autonomous driving control design, In Proceedings of the IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV-15), 2015.

- [Paden et al., 2016] B. Paden, M. Cap, S.Z. Yong, D. Yershov, and E. Frazzoli, A survey of motioni planning and control techniques for self-driving urban vehicles, IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles, 1(1): 33-55, 2016.